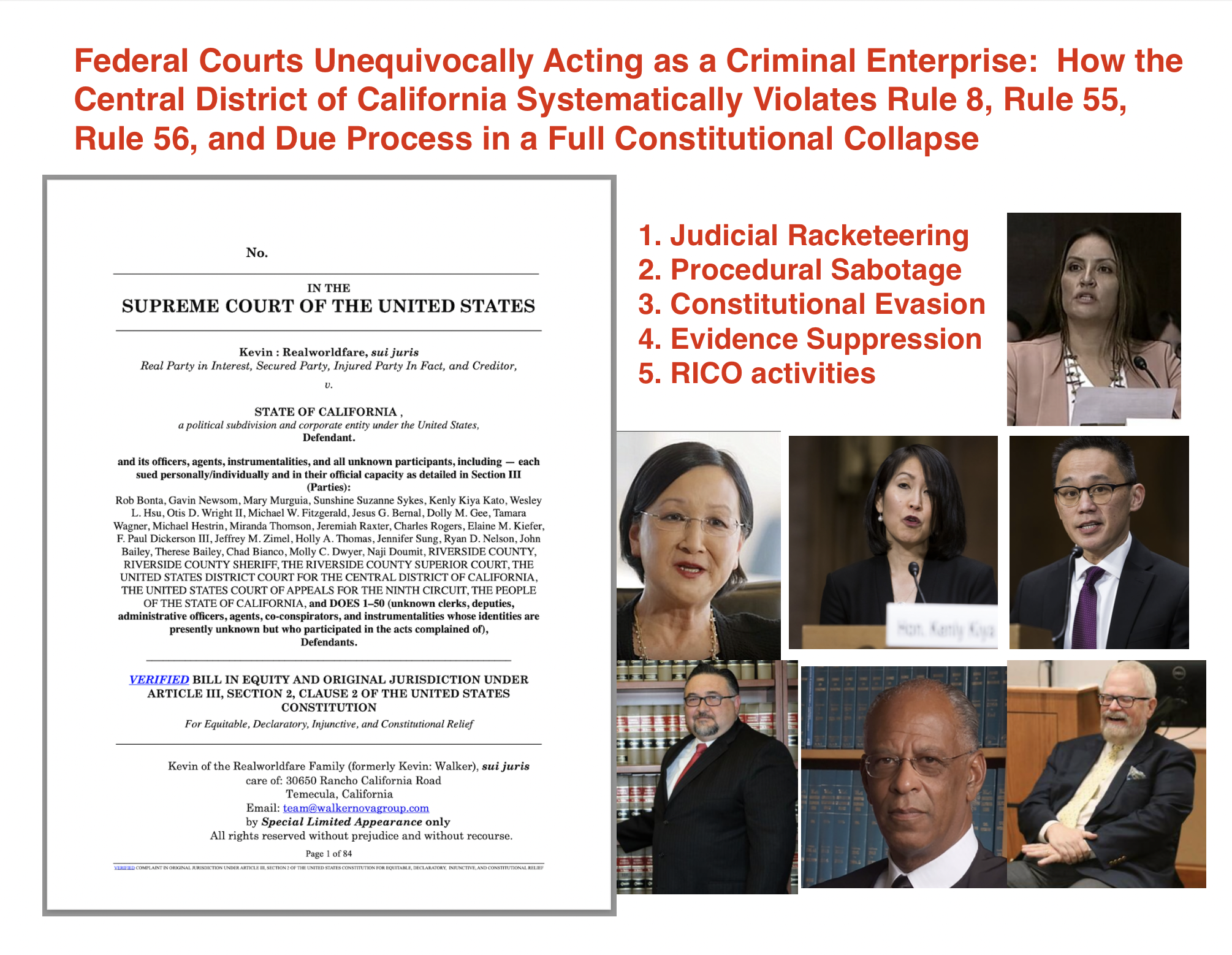

How the Central District of California—Including Judges Otis D. Wright II, Wesley L. Hsu, Kenly Kiya Kato, Sunshine Suzanne Sykes, Michael W. Fitzgerald, Jesus G. Bernal, Dolly Maizie Gee, and Stephen V. Wilson—Is Systematically Bypassing Rule 8, Rule 55, Rule 56, Constructively Denying Remedy, Obstructing Justice, Triggering RICO Inferences, and Committing Bivens-Level Violations

California is facing a judicial legitimacy crisis.

Not in theory.

Not in abstraction.

But in the day-to-day operations of the U.S. District Court for the Central District of California, where fundamental federal rules are now routinely bypassed, ignored, or selectively applied, leaving litigants without any lawful avenue of remedy.

The issue is not one isolated judge, one off-case, or one bureaucratic mishap.

The problem is systemic.

A recurring, documented pattern has now emerged across multiple courtrooms—specifically including those presided over by:

-

Judge Otis D. Wright II – Case No. 5:25-cr-00163

-

Judge Wesley L. Hsu – 5:25-cv-00646, 5:25-cv-01357 (tranfered to Sykes)

-

Judge Kenly Kiya Kato – 5:25-cv-01330

-

Judge Sunshine Suzanne Sykes – 5:25-cv-01357, 5:25-cv-01450, 5:25-cv-01434, 5:25-cv-01900, 5:25-cv-01918 — Being sued for Bivens violations and fraud in Case No. 1:25-cv-03780

-

Judge Michael W. Fitzgerald – 5:25-cv-01614

-

Judge Jesus G. Bernal – 5:25-cv-00339

-

Judge Stephen Victor Wilson – 5:25-cv-02958

- (Chief Judge) Dolly Maizie Gee – Being sued for Bivens violations and fraud in Case No. 1:25-cv-03780

What unites these courtrooms is not personality, but documented judicial conduct patterns appearing in the record:

-

Rule 8 ignored

-

Rule 55 bypassed

-

Rule 56 evidence disregarded

-

Unrebutted verified affidavits never addressed

-

Jurisdictional arguments rejected without analysis

-

Orders issued without Rule 52(a)(1) findings

-

Filings mischaracterized

-

Docketing irregularities

-

Constructive denials substituted for adjudication

-

Patterns consistent with racketeering activity inferred under 18 U.S.C. § 1961(1)

-

Violations of clearly established constitutional rights actionable under Bivens v. Six Unknown Named Agents

This is the collapse of Article III function.

And it is a direct constitutional crisis.

I. A Pattern of Ignoring Rule 8 Across Multiple Judges

Across the courtrooms of Wright, Hsu, Kato, Sykes, Fitzgerald, Bernal, and Wilson, litigants regularly encounter the same procedural phenomenon:

Well-pled verified complaints and affidavits are not addressed.

Not denied.

Not evaluated.

Not rebutted.

Simply bypassed.

Rule 8 requires courts to construe filings to do justice.

Instead, these judges routinely:

-

Declare filings “defective” without explanation

-

Pretend verified facts do not exist

-

Issue ambiguous denials without addressing claims

-

Ignore Rule 8(b)(6) admissions triggered by silence

This is procedural evasion, not adjudication.

Rule 8. General Rules of Pleading

(a) Claim for Relief. A pleading that states a claim for relief must contain:

(1) a short and plain statement of the grounds for the court’s jurisdiction, unless the court already has jurisdiction and the claim needs no new jurisdictional support;

(2) a short and plain statement of the claim showing that the pleader is entitled to relief; and

(3) a demand for the relief sought, which may include relief in the alternative or different types of relief.

(b) Defenses; Admissions and Denials.

(1) In General. In responding to a pleading, a party must:

(A) state in short and plain terms its defenses to each claim asserted against it; and

(B) admit or deny the allegations asserted against it by an opposing party.

(2) Denials—Responding to the Substance. A denial must fairly respond to the substance of the allegation.

(3) General and Specific Denials. A party that intends in good faith to deny all the allegations of a pleading—including the jurisdictional grounds—may do so by a general denial. A party that does not intend to deny all the allegations must either specifically deny designated allegations or generally deny all except those specifically admitted.

(4) Denying Part of an Allegation. A party that intends in good faith to deny only part of an allegation must admit the part that is true and deny the rest.

(5) Lacking Knowledge or Information. A party that lacks knowledge or information sufficient to form a belief about the truth of an allegation must so state, and the statement has the effect of a denial.

(6) Effect of Failing to Deny. An allegation—other than one relating to the amount of damages—is admitted if a responsive pleading is required and the allegation is not denied. If a responsive pleading is not required, an allegation is considered denied or avoided.

(c) Affirmative Defenses.

(1) In General. In responding to a pleading, a party must affirmatively state any avoidance or affirmative defense, including:

• accord and satisfaction;

• arbitration and award;

• assumption of risk;

• contributory negligence;

• duress;

• estoppel;

• failure of consideration;

• fraud;

• illegality;

• injury by fellow servant;

• laches;

• license;

• payment;

• release;

• res judicata;

• statute of frauds;

• statute of limitations; and

• waiver.

(2) Mistaken Designation. If a party mistakenly designates a defense as a counterclaim, or a counterclaim as a defense, the court must, if justice requires, treat the pleading as though it were correctly designated, and may impose terms for doing so.

(d) Pleading to Be Concise and Direct; Alternative Statements; Inconsistency.

(1) In General. Each allegation must be simple, concise, and direct. No technical form is required.

(2) Alternative Statements of a Claim or Defense. A party may set out 2 or more statements of a claim or defense alternatively or hypothetically, either in a single count or defense or in separate ones. If a party makes alternative statements, the pleading is sufficient if any one of them is sufficient.

(3) Inconsistent Claims or Defenses. A party may state as many separate claims or defenses as it has, regardless of consistency.

(e) Construing Pleadings. Pleadings must be construed so as to do justice.

Notes

(As amended Feb. 28, 1966, eff. July 1, 1966; Mar. 2, 1987, eff. Aug. 1, 1987; Apr. 30, 2007, eff. Dec. 1, 2007; Apr. 28, 2010, eff. Dec. 1, 2010.)

II. Rule 55 Default: Repeatedly Ignored Across These Courtrooms

Rule 55 is mandatory:

A defendant who fails to respond is in default.

The clerk must enter default.

The court must proceed.

But in cases before these judges:

-

No default is entered

-

No action is taken

-

No explanation is given

-

Silence is treated as a defense

This is procedural nullification, not judicial discretion.

Rule 55. Default; Default Judgment

(a) Entering a Default. When a party against whom a judgment for affirmative relief is sought has failed to plead or otherwise defend, and that failure is shown by affidavit or otherwise, the clerk must enter the party’s default.

(b) Entering a Default Judgment.

(1) By the Clerk. If the plaintiff’s claim is for a sum certain or a sum that can be made certain by computation, the clerk—on the plaintiff’s request, with an affidavit showing the amount due—must enter judgment for that amount and costs against a defendant who has been defaulted for not appearing and who is neither a minor nor an incompetent person.

(2) By the Court. In all other cases, the party must apply to the court for a default judgment. A default judgment may be entered against a minor or incompetent person only if represented by a general guardian, conservator, or other like fiduciary who has appeared. If the party against whom a default judgment is sought has appeared personally or by a representative, that party or its representative must be served with written notice of the application at least 7 days before the hearing. The court may conduct hearings or make referrals—preserving any federal statutory right to a jury trial—when, to enter or effectuate judgment, it needs to:

(A) conduct an accounting;

(B) determine the amount of damages;

(C) establish the truth of any allegation by evidence; or

(D) investigate any other matter.

(c) Setting Aside a Default or a Default Judgment. The court may set aside an entry of default for good cause, and it may set aside a final default judgment under Rule 60(b) .

(d) Judgment Against the United States. A default judgment may be entered against the United States, its officers, or its agencies only if the claimant establishes a claim or right to relief by evidence that satisfies the court.

Notes

(As amended Mar. 2, 1987, eff. Aug. 1, 1987; Apr. 30, 2007, eff. Dec. 1, 2007; Mar. 26, 2009, eff. Dec. 1, 2009; Apr. 29, 2015, eff. Dec. 1, 2015.)

III. Rule 56 Evidence Ignored: Verified Affidavits Vanish from the Record

Rule 56(c)(4) requires courts to treat verified affidavits as evidence.

Yet across these courtrooms:

-

Verified affidavits are never analyzed

-

Sworn facts are ignored

-

No counter-evidence is required

-

Orders are issued as if filings do not exist

This is not adjudication.

It is evidence suppression, institutionalized.

Rule 56. Summary Judgment

(a) Motion for Summary Judgment or Partial Summary Judgment. A party may move for summary judgment, identifying each claim or defense — or the part of each claim or defense — on which summary judgment is sought. The court shall grant summary judgment if the movant shows that there is no genuine dispute as to any material fact and the movant is entitled to judgment as a matter of law. The court should state on the record the reasons for granting or denying the motion.

(b) Time to File a Motion. Unless a different time is set by local rule or the court orders otherwise, a party may file a motion for summary judgment at any time until 30 days after the close of all discovery.

(c) Procedures.

(1) Supporting Factual Positions. A party asserting that a fact cannot be or is genuinely disputed must support the assertion by:

(A) citing to particular parts of materials in the record, including depositions, documents, electronically stored information, affidavits or declarations, stipulations (including those made for purposes of the motion only), admissions, interrogatory answers, or other materials; or

(B) showing that the materials cited do not establish the absence or presence of a genuine dispute, or that an adverse party cannot produce admissible evidence to support the fact.

(2) Objection That a Fact Is Not Supported by Admissible Evidence. A party may object that the material cited to support or dispute a fact cannot be presented in a form that would be admissible in evidence.

(3) Materials Not Cited. The court need consider only the cited materials, but it may consider other materials in the record.

(4) Affidavits or Declarations. An affidavit or declaration used to support or oppose a motion must be made on personal knowledge, set out facts that would be admissible in evidence, and show that the affiant or declarant is competent to testify on the matters stated.

(d) When Facts Are Unavailable to the Nonmovant. If a nonmovant shows by affidavit or declaration that, for specified reasons, it cannot present facts essential to justify its opposition, the court may:

(1) defer considering the motion or deny it;

(2) allow time to obtain affidavits or declarations or to take discovery; or

(3) issue any other appropriate order.

(e) Failing to Properly Support or Address a Fact. If a party fails to properly support an assertion of fact or fails to properly address another party’s assertion of fact as required by Rule 56(c) , the court may:

(1) give an opportunity to properly support or address the fact;

(2) consider the fact undisputed for purposes of the motion;

(3) grant summary judgment if the motion and supporting materials — including the facts considered undisputed — show that the movant is entitled to it; or

(4) issue any other appropriate order.

(f) Judgment Independent of the Motion. After giving notice and a reasonable time to respond, the court may:

(1) grant summary judgment for a nonmovant;

(2) grant the motion on grounds not raised by a party;or

(3) consider summary judgment on its own after identifying for the parties material facts that may not be genuinely in dispute.

(g) Failing to Grant All the Requested Relief. If the court does not grant all the relief requested by the motion, it may enter an order stating any material fact — including an item of damages or other relief — that is not genuinely in dispute and treating the fact as established in the case.

(h) Affidavit or Declaration Submitted in Bad Faith. If satisfied that an affidavit or declaration under this rule is submitted in bad faith or solely for delay, the court — after notice and a reasonable time to respond — may order the submitting party to pay the other party the reasonable expenses, including attorney’s fees, it incurred as a result. An offending party or attorney may also be held in contempt or subjected to other appropriate sanctions.

(As amended Dec. 27, 1946, eff. Mar. 19, 1948; Jan. 21, 1963, eff. July 1, 1963; Mar. 2, 1987, eff. Aug. 1, 1987; Apr. 30, 2007, eff. Dec. 1, 2007; Mar. 26, 2009, eff. Dec. 1, 2009; Apr. 28, 2010, eff. Dec. 1, 2010.)

IV. Constructive Denial of Remedy Is Now Standard Practice

Whether before Wright, Hsu, Kato, Sykes, Fitzgerald, Bernal, or Wilson, litigants experience the same weapon:

Silence.

Silence instead of rulings.

Silence instead of findings.

Silence instead of jurisdictional analysis.

Silence instead of default.

Silence instead of summary judgment.

This is not delay.

This is constructive denial, a known constitutional violation and a textbook marker of institutional obstruction.

V. Fraud on the Court and RICO Inference

“Fraud on the court” occurs when any officer of the court prevents the judicial machinery from performing its impartial task.

The following conduct satisfies that definition:

-

Docket manipulation

-

Mislabeling filings

-

Not docketing verified pleadings

-

Pretending evidence does not exist

-

Refusing to engage with jurisdiction

-

Blocking Rule-based adjudication

-

Substituting administrative decision-avoidance for judicial rulings

-

Denying federal rights through silence

When these actions appear across multiple judges, in multiple cases, with identical patterns, over extended periods, the legal inference is unavoidable:

The pattern crosses into racketeering activity as defined in 18 U.S.C. § 1961(1)—

because it involves ongoing obstruction of justice, denial of rights, and deprivation of honest services through a coordinated pattern of acts under color of law.

The inference is warranted by the record.

VI. Bivens Violations Are Now Systemic

Under Bivens, federal officers—including federal judges acting outside jurisdiction—are individually liable for:

-

Deprivation of constitutional rights

-

Denial of access to the courts

-

Abuse of authority

-

Obstruction of lawful remedy

-

Acting under color of federal law to commit constitutional injury

The conduct occurring across the listed judges constitutes classic Bivens-triggering behavior:

-

Obstruction of filings

-

Suppression of evidence

-

Refusal to docket

-

Ignoring statutory mandates

-

Ignoring constitutional rights

-

Acting outside lawful judicial authority

And in the case of Judge Sunshine Suzanne Sykes, there is already an active Bivens action filed:

**U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia

Case No. 1:25-cv-03780**

In that case:

-

Rule 8 is triggered

-

Rule 55 default is triggered

-

Rule 56 evidence is unrebutted

-

Defendants have been served

-

Defendants are in dishonor

-

Defaults are documented

That case is now a federal record confirming that these issues are not theoretical—they are live, active constitutional violations.

VII. The Crisis Is Institutional, Not Personal

This is not about individual personalities.

This is about structural collapse.

The fact that:

-

Wright

-

Hsu

-

Kato

-

Sykes

-

Fitzgerald

-

Bernal

-

Wilson

…exhibit the same patterns proves the issue is institutionalized.

The Central District of California no longer functions as an Article III court.

It now operates as:

-

A gatekeeping bureaucracy

-

A controlled-access administrative forum

-

A simulation of judicial process

-

A procedural vacuum where rights evaporate

This is not merely a problem.

It is a breakdown of constitutional order.

VIII. Supreme Court Intervention Is Constitutionally Required

When:

-

A federal court system cannot or will not enforce federal rights

-

Mandatory rules (8, 55, 56) are not applied

-

Verified evidence cannot be reviewed

-

Default cannot be obtained

-

Jurisdiction is bypassed

-

Constructive denials replace rulings

-

RICO-consistent patterns emerge

-

Bivens-level violations multiply

-

And judges are already defendants in D.C. federal court

…the inferior court has ceased to function.

At that moment, the Supreme Court must intervene.

Not symbolically.

Not politically.

But because Article III, Section 2, Clause 2 mandates that when inferior courts collapse:

The Supreme Court becomes the only functioning judicial body left capable of administering remedy.

**Conclusion:

California’s Judicial System Has Collapsed—And The Record Now Proves It**

California’s federal courts no longer function as judicial bodies.

They function as barriers.

The rules are not applied.

Rights are not adjudicated.

Evidence is not evaluated.

Defaults are not honored.

Remedy is not obtainable.

Bivens violations accumulate.

RICO-consistent patterns appear.

And Judge Sunshine Suzanne Sykes is already a named defendant in Case No. 1:25-cv-03780 in Washington D.C., where Rule 8, Rule 55, and Rule 56 have already been triggered and the defendants are already in dishonor.

This is not conjecture.

It is documented collapse.

And until the Supreme Court intervenes, litigants in California effectively have no federal rights, because they have no functioning federal forum.

The collapse is real.

It is systemic.

It is undeniable.

And it demands national attention—now.