A Clear Declaration of Rights

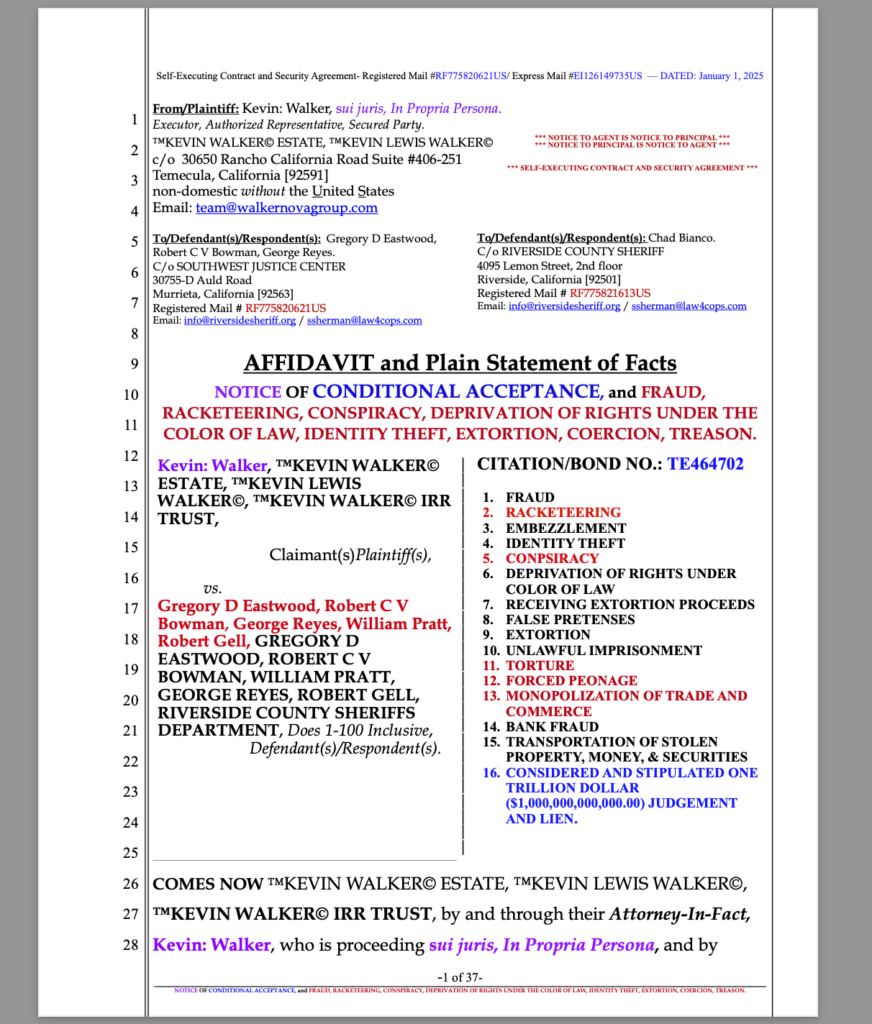

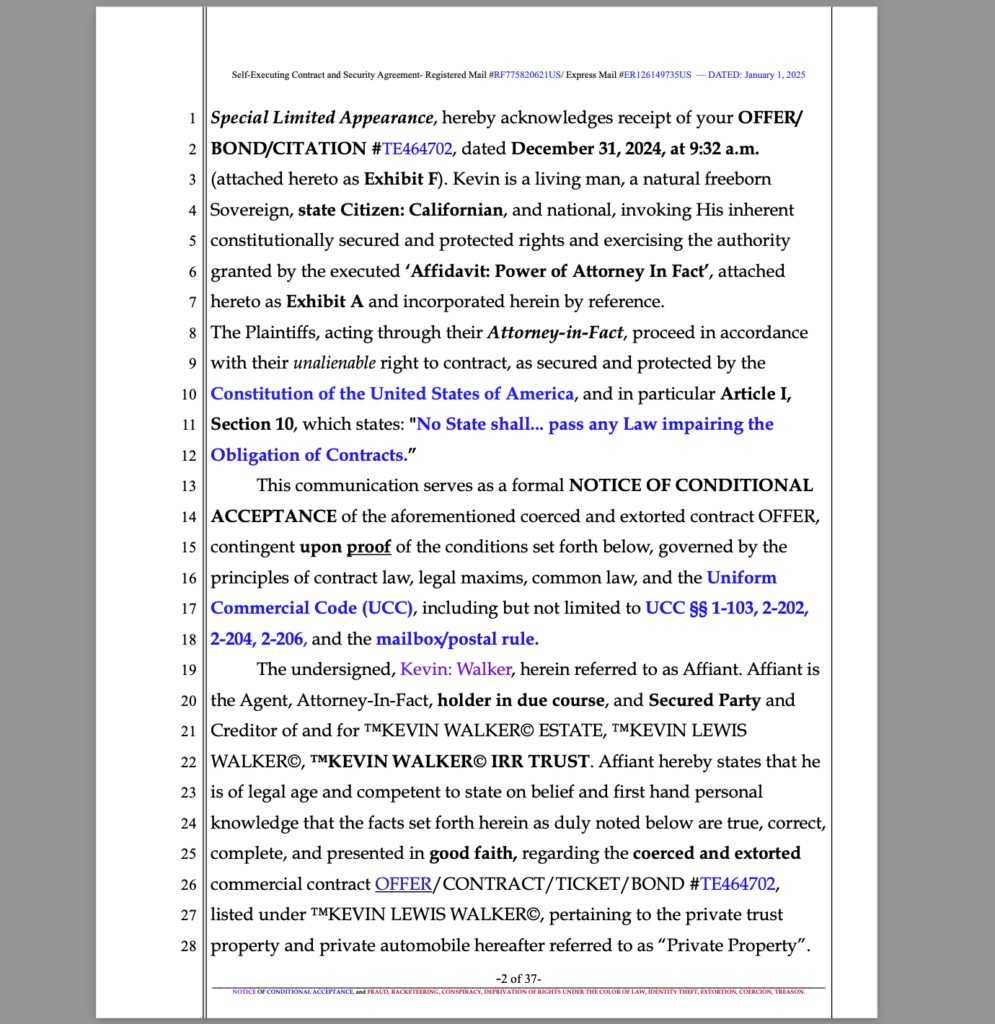

At the heart of this legal strategy lies a fundamental principle: no one can be compelled into a contract they did not knowingly, willingly, and intentionally enter. Kevin: Walker, acting as Agent, Attorney-In-Fact, and Secured Party for the ™KEVIN LEWIS WALKER© Estate and related entities, issued a formal Notice of Conditional Acceptance to challenge what he identifies as a coerced and extorted contract. This document not only places the burden of proof on the opposing party but also serves as a self-executing contract and security agreement, creating enforceable obligations through the application of the mailbox rule and UCC provisions.

The Right to Travel is central to this case, as Walker asserts this unalienable gift, grounded in natural law, protected by the Constitution, and affirmed through numerous legal precedents. The right to travel is not a privilege requiring licensing, registration, or insurance; rather, it is an inherent right beyond the reach of man-made laws or statutes masquerading as authority.

Traveling Is Not a Privilege: Foundational Legal Precedents

The fundamental right to travel has been upheld in numerous landmark cases:

- Chicago Coach Co. v. City of Chicago, 337 Ill. 200, 169 N.E. 22 affirms that no state government has the power to deny passage on highways or waterways, regardless of whether the individual is traveling for business or recreation.

- Kent v. Dulles, 357 U.S. 116, 127 establishes that the right to travel is part of the “liberty” guaranteed under the Fifth Amendment, a right emerging as early as the Magna Carta.

- In Re Archy (1858), 9 C. 47 defines traveling as the act of passing from place to place, an inherent activity that does not depend on statutory permissions.

These precedents unequivocally distinguish between travel, a natural right, and the regulated use of public highways for commercial purposes, which may be subject to licensing and other restrictions.

- “No State government entity has the power to allow or deny passage on the highways, byways, nor waterways… transporting his vehicles and personal property for either recreation or business, but by being subject only to local regulation i.e., safety, caution, traffic lights, speed limits, etc. Travel is not a privilege requiring, licensing, vehicle registration, or forced insurances.” Chicago Coach Co. v. City of Chicago, 337 Ill. 200, 169 N.E. 22.

- The fundamental Right to travel is NOT a Privilege, it’s a gift granted by your Creator and restated by our founding fathers as Unalienable and cannot be taken by any Man / Government made Law or color of law known as a private “Code” (secret) or a “Statute.”

- “Traveling is passing from place to place–act of performing journey; and traveler is person who travels.” In Re Archy (1858), 9 C. 47.

- “Right of transit through each state, with every species of property known to constitution of United States, and recognized by that paramount law, is secured by that instrument to each citizen, and does not depend upon uncertain and changeable ground of mere comity.” In Re Archy (1858), 9 C. 47.

- Freedom to travel is, indeed, an important aspect of the citizen’s “liberty”. We are first concerned with the extent, if any, to which Congress has authorized its curtailment. (Road) Kent v. Dulles, 357 U.S. 116, 127.

- The right to travel is a part of the “liberty” of which the citizen cannot be deprived without due process of law under the Fifth Amendment. So much is conceded by the solicitor general. In Anglo Saxon law that right was emerging at least as early as Magna Carta. Kent v. Dulles, 357 U.S. 116, 125.

- “Even the legislature has no power to deny to a citizen the right to travel upon the highway and transport his property in the ordinary course of his business or pleasure, though this right may be regulated in accordance with public interest and convenience. Chicago Coach Co. v. City of Chicago, 337 Ill. 200, 169 N.E. 22, 206.

- “… It is now universally recognized that the state does possess such power [to impose such burdens and limitations upon private carriers when using the public highways for the transaction of their business] with respect to common carriers using the public highways for the transaction of their business in the transportation of persons or property for hire. That rule is stated as follows by the supreme court of the United States: ‘A citizen may have, under the fourteenth amendment, the right to travel and transport his property upon them (the public highways) by auto vehicle, but he has no right to make the highways his place of business by using them as a common carrier for hire. Such use is a privilege which may be granted or withheld by the state in its discretion, without violating either the due process clause or the equal protection clause.’ (Buck v. Kuykendall, 267 U. S. 307 [38 A. L. R. 286, 69 L. Ed. 623, 45 Sup. Ct. Rep. 324].

- “The right of a citizen to travel upon the highway and transport his property thereon in the ordinary course of life and business differs radically an obviously from that of one who makes the highway his place of business and uses it for private gain, in the running of a stage coach or omnibus. The former is the usual and ordinary right of a citizen, a right common to all; while the latter is special, unusual and extraordinary. As to the former, the extent of legislative power is that of regulation; but as to the latter its power is broader; the right may be wholly denied, or it may be permitted to some and denied to others, because of its extraordinary nature. This distinction, elementary and fundamental in character, is recognized by all the authorities.”

- “ Even the legislature has no power to deny to a citizen the right to travel upon the highway and transport his/her property in the ordinary course of his business or pleasure, though this right may be regulated in accordance with the public interest and convenience.” [“regulated” means traffic safety enforcement, stop lights, signs etc.]—Chicago Motor Coach v. Chicago, 169 NE 22.

- “The claim and exercise of a constitutional right cannot be converted into a crime.”—Miller v. U.S., 230 F 2d 486, 489

- “Owner has constitutional right to use and enjoyment of his property.” Simpson v. Los Angeles (1935), 4 C.2d 60, 47 P.2d 474.

- “There can be no sanction or penalty imposed upon one because of this exercise of constitutional rights.” —Sherar v. Cullen, 481 F. 945

- The right of the citizen to travel upon the highway and to transport his property thereon, in the ordinary course of life and business, differs radically and obviously from that of one who makes the highway his place of business for private gain in the running of a stagecoach or omnibus.”— State vs. City of Spokane, 186 P. 864.

- ”The right of the citizen to travel upon the public highways and to transport his/her property thereon either by carriage or automobile, is not a mere privilege which a city [or State] may prohibit or permit at will, but a common right which he/she has under the right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” —Thompson v. Smith, 154 SE 579.

- “The right of the Citizen to travel upon the public highways and to transport his property thereon, in the ordinary course of life and business, is a common right which he has under the right to enjoy life and liberty, to acquire and possess property, and to pursue happiness and safety. It includes the right, in so doing, to use the ordinary and usual conveyances of the day, and under the existing modes of travel, includes the right to drive a horse drawn carriage or wagon thereon or to operate an automobile thereon, for the usual and ordinary purpose of life and business.”— Thompson vs. Smith, supra.; Teche Lines vs. Danforth, Miss., 12 S.2d 784

- “The use of the highways for the purpose of travel and transportation is not a mere privilege, but a common and fundamental Right of which the public and the individual cannot be rightfully deprived.”—Chicago Motor Coach vs. Chicago, 169 NE 22;Ligare vs. Chicago, 28 NE 934;Boon vs. Clark, 214 SSW 607;25 Am.Jur. (1st) Highways Sect.163.

- “The right to b is part of the Liberty of which a citizen cannot deprived without due process of law under the Fifth Amendment. This Right was emerging as early as the Magna Carta.” — Kent vs. Dulles, 357 US 116 (1958)

- “The state cannot diminish Rights of the people.” —Hurtado vs. California, 110 US 516.

- ””Personal liberty largely consists of the Right of locomotion — to go where and when one pleases — only so far restrained as the Rights of others may make it necessary for the welfare of all other citizens. The Right of the Citizen to travel upon the public highways and to transport his property thereon, by horse drawn carriage, wagon, or automobile, is not a mere privilege which may be permitted or prohibited at will, but the common Right which he has under his Right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. Under this Constitutional guarantee one may, therefore, under normal conditions, travel at his inclination along the public highways or in public places, and while conducting himself in an orderly and decent manner, neither interfering with nor disturbing another’s Rights, he will be protected, not only in his person, but in his safe conduct.” —II Am.Jur. (1st) Constitutional Law, Sect.329, p.1135

Use defines classification:

-

- It is well established law that the highways of the state are public property, and their primary and preferred use is for private purposes, and that their use for purposes of gain is special and extraordinary which, generally at least, the legislature may prohibit or condition as it sees fit.” Stephenson vs. Rinford, 287 US 251; Pachard vs Banton, 264 US 140, and cases cited; Frost and F. Trucking Co. vs. Railroad Commission, 271 US 592; Railroad commission vs. Inter-City Forwarding Co., 57 SW.2d 290; Parlett Cooperative vs. Tidewater Lines, 164 A. 313

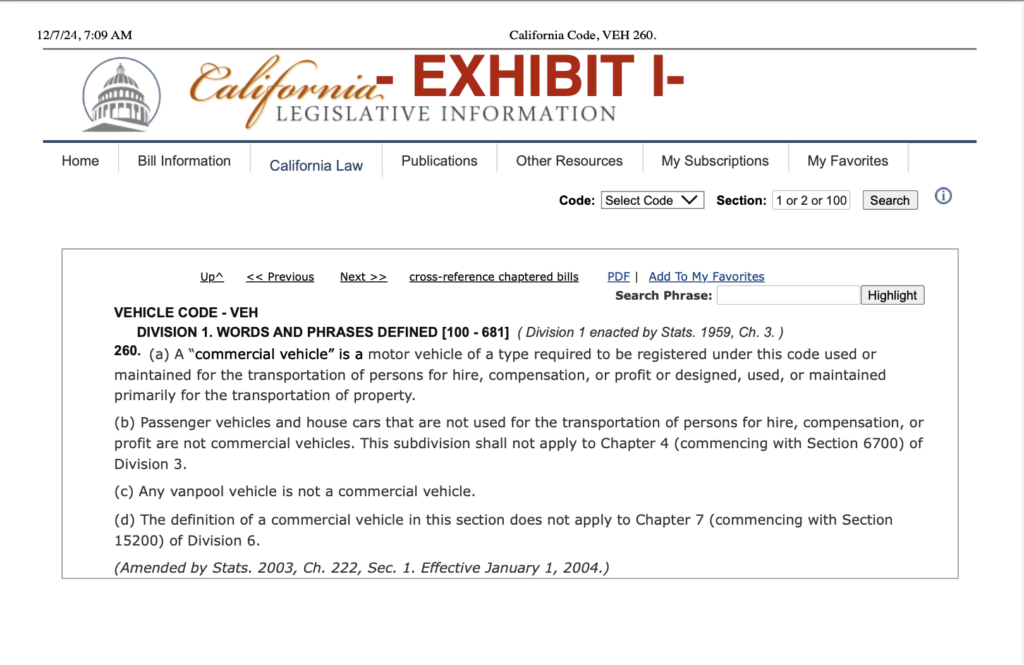

- The California Motor Vehicle Code, section 260: Private cars/vans etc. not in commerce / for profit, are immune to registration fees:

- (a) A “commercial vehicle” is a vehicle of a type REQUIRED to be REGISTERED under this code”.

- (b) “Passenger vehicles which are not used for the transportation of persons for hire, compensation or profit, and housecars, are not commercial vehicles”.

- (c) “a vanpool vehicle is not a commercial vehicle.”

- 18 U.S. Code § 31 – Definition, expressly stipulates, ”The term “motor vehicle” means every description of carriage or other contrivance propelled or drawn by mechanical power and used for commercial purposes on the highways in the transportation of passengers, passengers and property, or property or cargo”.

- A vehicle not used for commercial activity is a “consumer goods”, …it is NOT a type of vehicle required to be registered and “use tax” paid of which the tab is evidence of receipt of the tax.” Bank of Boston vs Jones, 4 UCC Rep. Serv. 1021, 236 A2d 484, UCC PP 9-109.14.

- “ The ‘privilege’ of using the streets and highways by the operation thereon of motor carriers for hire can be acquired only by permission or license from the state or its political subdivision. “—Black’s Law Dictionary, 5th ed, page 830.

- “It is held that a tax upon common carriers by motor vehicles is based upon a reasonable classification, and does not involve any unconstitutional discrimination, although it does not apply to private vehicles, or those used by the owner in his own business, and not for hire.” Desser v. Wichita, (1915) 96 Kan. 820; Iowa Motor Vehicle Asso. v. Railroad Comrs., 75 A.L.R. 22.

- “Thus self-driven vehicles are classified according to the use to which they are put rather than according to the means by which they are propelled.” Ex Parte Hoffert, 148 NW 20.

- In view of this rule a statutory provision that the supervising officials “may” exempt such persons when the transportation is not on a commercial basis means that they “must” exempt them.” State v. Johnson, 243 P. 1073; 60 C.J.S. section 94 page 581.

- “The use to which an item is put, rather than its physical characteristics, determine whether it should be classified as “consumer goods” under UCC 9- 109(1) or “equipment” under UCC 9-109(2).” Grimes v Massey Ferguson, Inc., 23 UCC Rep Serv 655; 355 So.2d 338 (Ala., 1978).

- “Under UCC 9-109 there is a real distinction between goods purchased for personal use and those purchased for business use. The two are mutually exclusive and the principal use to which the property is put should be considered as determinative.” James Talcott, Inc. v Gee, 5 UCC Rep Serv 1028; 266 Cal.App.2d 384, 72 Cal.Rptr. 168 (1968).

- “The classification of goods in UCC 9-109 are mutually exclusive.” McFadden v Mercantile-Safe Deposit & Trust Co., 8 UCC Rep Serv 766; 260 Md 601, 273 A.2d 198 (1971).

- “The classification of “goods” under [UCC] 9-109 is a question of fact.” Morgan County Feeders, Inc. v McCormick, 18 UCC Rep Serv 2d 632; 836 P.2d 1051 (Colo. App., 1992).

- “The definition of “goods” includes an automobile.” Henson v Government Employees Finance & Industrial Loan Corp., 15 UCC Rep Serv 1137; 257 Ark 273, 516 S.W.2d 1 (1974).

The Foundation of Conditional Acceptance

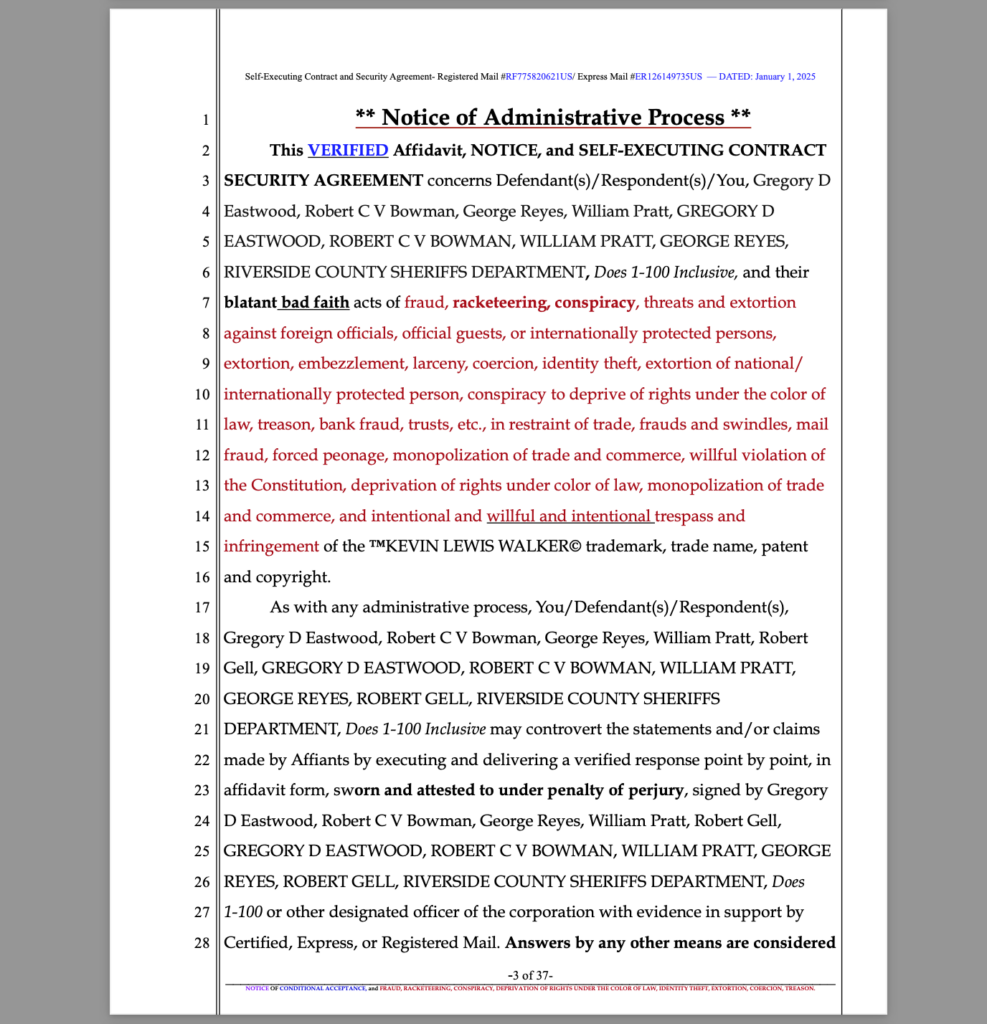

Under UCC §§ 1-103, 2-202, 2-204, and 2-206, a conditional acceptance operates as a counteroffer, requiring the other party to provide evidence or rebuttal before proceeding further. Kevin: Walker’s notice demands verified responses to each claim, sworn under penalty of perjury, and explicitly rejects non-response or incomplete answers. This framework shifts the power dynamics, compelling the opposing party to address the claims point by point or risk tacit acquiescence.

By invoking these provisions, Walker reaffirms the distinction between private individuals exercising their right to travel and entities engaged in commerce. As the courts have stated, “The right of a citizen to travel upon the highway and transport his property thereon in the ordinary course of life and business differs radically…from that of one who makes the highway his place of business.” (Chicago Motor Coach v. Chicago, 169 NE 22).

Administrative Process and Remedy

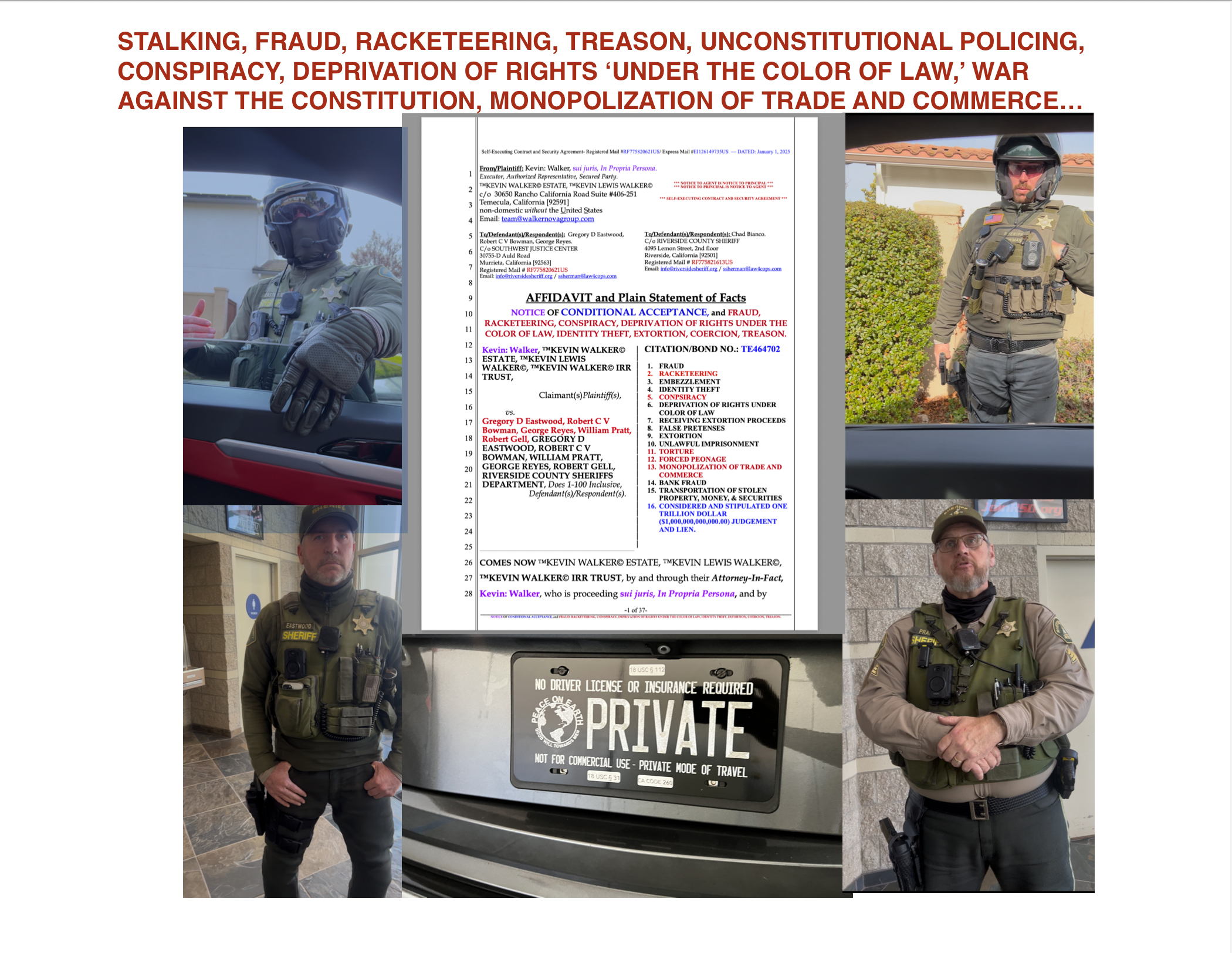

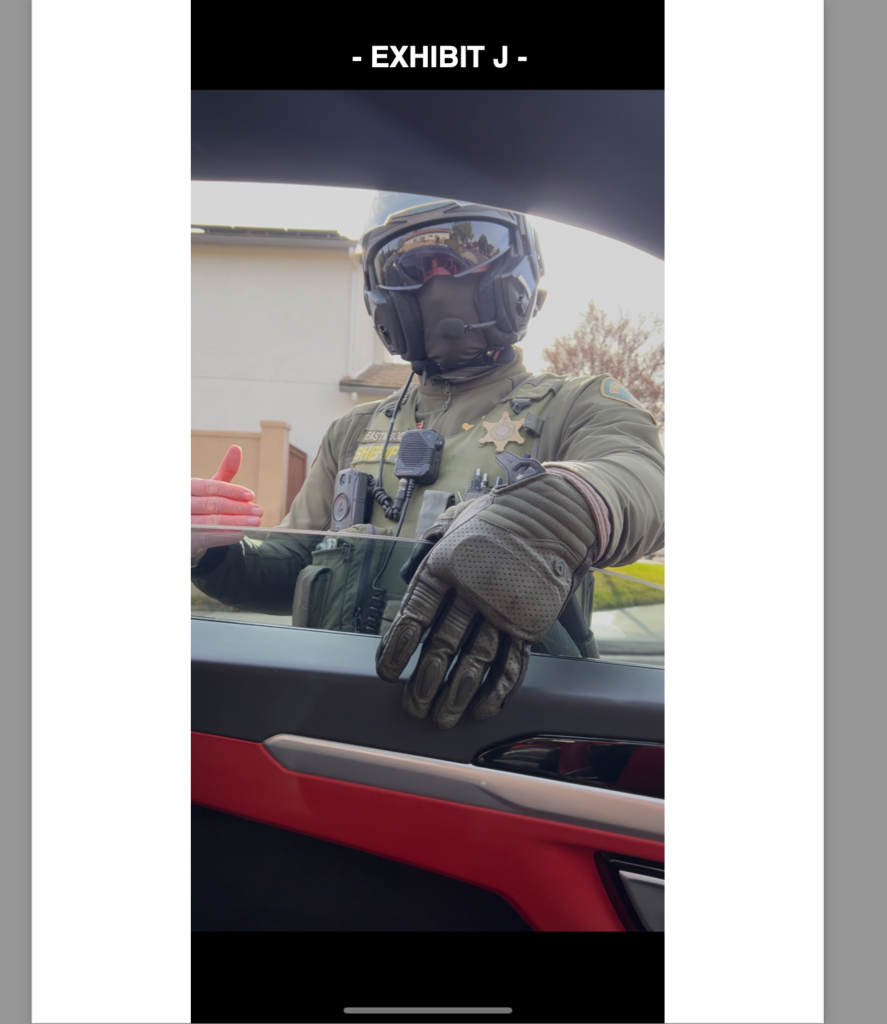

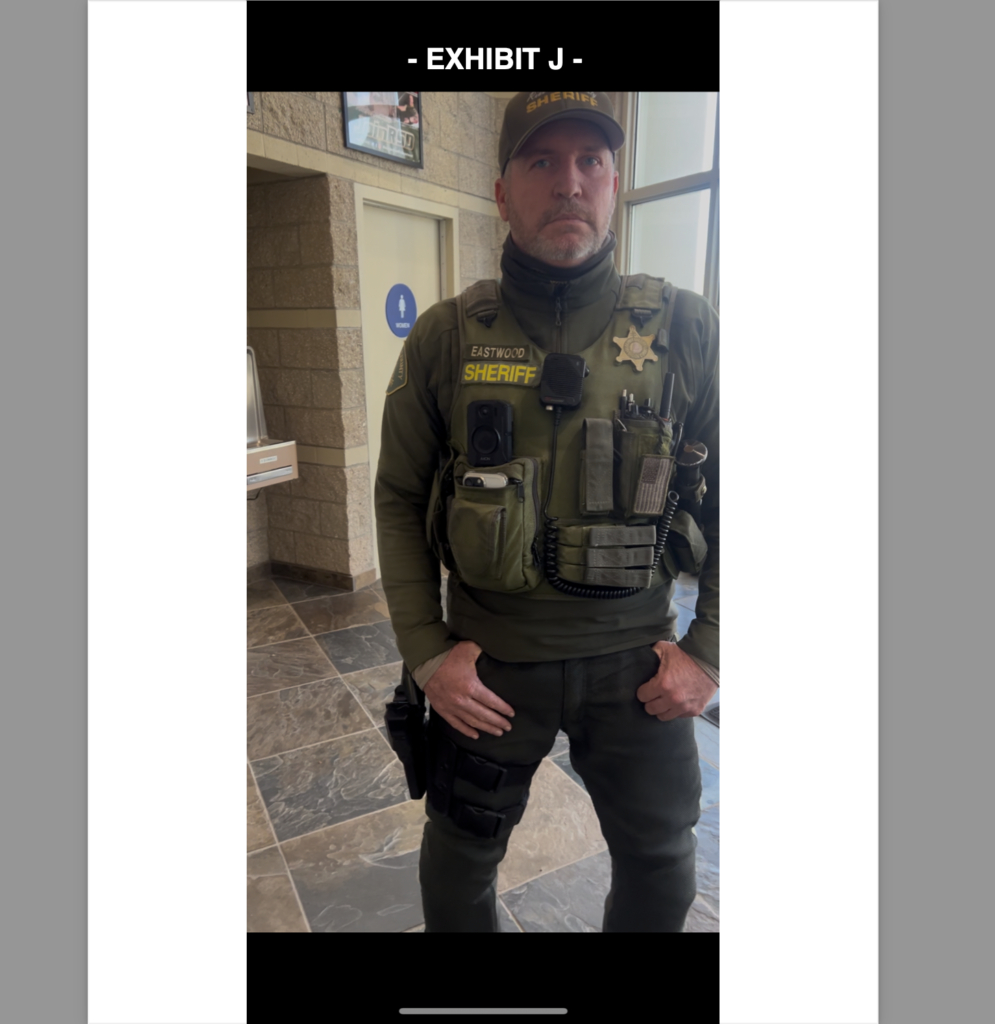

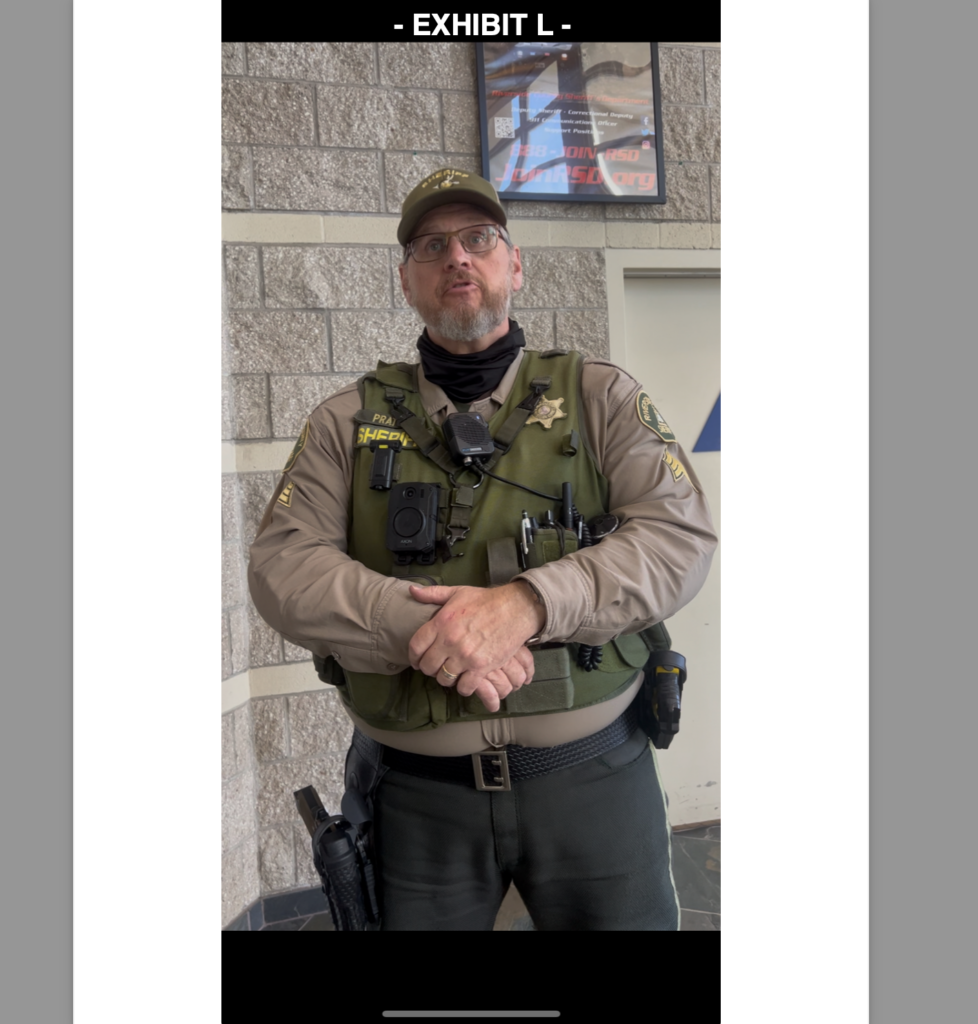

Affiant Kevin: Walker initiated this administrative process in response to actions by Defendants Gregory D. Eastwood, Robert C. V. Bowman, Sergeant William Pratt, George Reyes, and the Riverside County Sheriff’s Department. The allegations include fraud, racketeering, coercion, deprivation of rights under color of law, and conspiracy.

By invoking the administrative process, the Affiant creates a pathway for resolution outside of traditional court proceedings, leveraging the Defendants’ silence or failure to rebut as admission of guilt. The Notice of Conditional Acceptance, therefore, becomes a potent tool for holding public officials accountable for violations of individual rights.

Traveling Versus Driving: A Matter of Jurisdiction

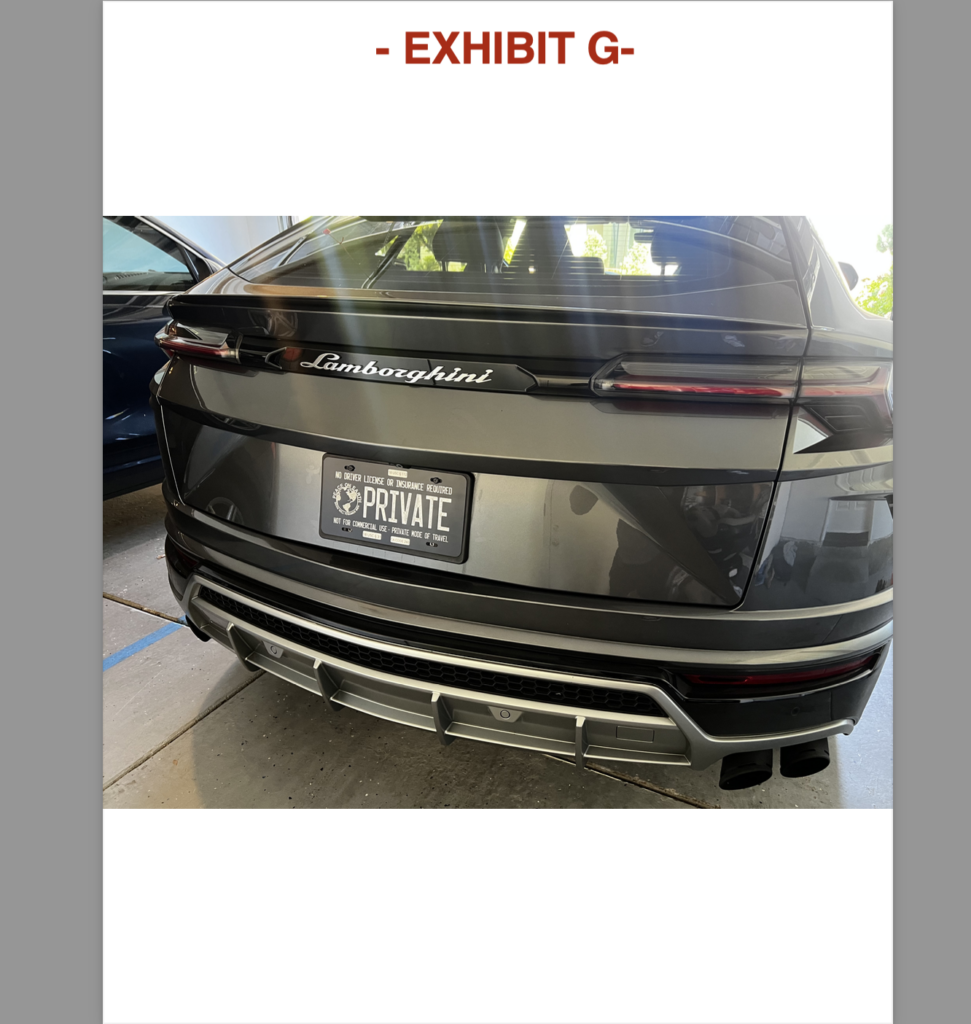

Central to Kevin: Walker’s claims is the distinction between private travel and commercial driving. Walker asserts that the requirement for a driver’s license applies exclusively to those engaged in commerce. As a private individual traveling for personal purposes in his private automobile, Kevin is not subject to statutory regulations designed for commercial activity, as his the private automobile is clearly classified as “private.”

The private automobile, identified by a “PRIVATE” plate and devoid of state registration, stands as a declaration of his non-commercial/private status.

Prima Facie Evidence of Misconduct

The Affidavit serves as prima facie evidence of misconduct by the named Defendants, citing violations of federal statutes, including 18 U.S.C. §§ 241 and 242 (conspiracy and deprivation of rights under color of law). Specific claims include:

- Fraud and Racketeering: Systematic exploitation of statutory frameworks to impose unlawful obligations.

- Identity Theft and Extortion: Unauthorized use of the Affiant’s name and estate to coerce compliance.

- Deprivation of Rights: Violation of constitutional protections, including the right to travel freely.

The Self-Executing Contract and Security Agreement

One of the most compelling aspects of the Notice is its designation as a self-executing contract and security agreement, authorized under Article 9 of the UCC. This designation establishes an immediate lien against the Defendants, binding them to the terms set forth by the Affiant. By invoking the mailbox rule—a legal doctrine stating that acceptance is effective upon dispatch—the Affiant ensures that the agreement becomes enforceable the moment it is mailed.

Legal Precedents and Maxims

Walker’s position draws on longstanding legal principles and precedents:

- Hale v. Henkel (1905): Affirming the right of individuals to contract freely and to refuse compliance with unwarranted state demands.

- Adams v. Lindsell (1818): Establishing the mailbox rule, which underpins the enforceability of the self-executing contract.

- UCC § 1-308: Reserving the right to not be compelled into unrevealed contracts or obligations.

These references underscore the Plaintiffs’ (Kevin’s) assertion of his natural and common law rights, as well as his rejection of any implied or coerced obligations.

Implications for Sovereignty and Justice

This case is a powerful reminder of the fragility of coercive systems when challenged by informed and precise legal action. Kevin: Walker’s Affidavit represents a bold assertion of sovereignty, exposing systemic overreach and leveraging legal principles to uphold the enduring power of truth, equity, and justice.

For individuals seeking to reclaim their sovereignty and navigate the complex interplay of common law, statutory law, and the UCC, this case serves as both inspiration and a call to action. As the courts have repeatedly affirmed, the right to travel is unalienable, fundamental, and above all, protected.