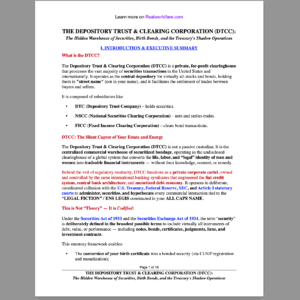

Introduction

It is a little-known but indisputable fact that every court case in the United States is also a financial transaction. The public is led to believe that proceedings are purely about justice, but statutes and court rules reveal that each case is underwritten by bonds, deposits, and securities. These instruments follow the same framework used in federal procurement — bid bonds, performance bonds, and payment bonds — and are monetized through the Court Registry Investment System (CRIS) and related Treasury accounts.

Congress has already codified this structure. 28 U.S.C. § 2041 requires that “all moneys paid into any court of the United States, or received by its officers, in any case pending or adjudicated in such court, shall be forthwith deposited with the Treasurer of the United States, or a designated depositary, in the name and to the credit of such court.” Further, 28 U.S.C. § 2042 confirms that these funds remain on deposit until withdrawn by court order, and that “any claimant entitled to such money may, on petition to the court and upon notice to the United States attorney, obtain an order directing payment to him.”

The federal judiciary’s own financial management policy directs clerks to deposit these registry funds into CRIS, where they are invested in U.S. Treasury securities and accrue interest under 28 U.S.C. § 2045. This transforms every case into a financial instrument, silently monetized under CUSIP identifiers and traded as part of the broader securities market.

This system is inseparable from the emergency financial framework created in the 20th century:

- Federal Reserve Act (1913, codified at 12 U.S.C. §§ 221 et seq.): Established Federal Reserve notes as obligations of the United States under 12 U.S.C. § 411, and, under 12 U.S.C. § 412, authorized Federal Reserve banks to issue such notes only upon pledging collateral security (notes, drafts, bills of exchange, or other instruments). This confirms that all currency is issued against pledged collateral — the same mechanism mirrored in court bonding.

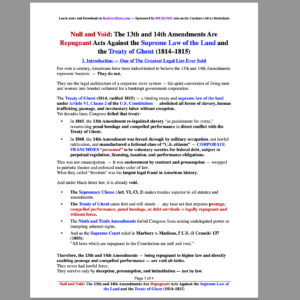

- Trading with the Enemy Act (1917, codified at 50 U.S.C. §§ 4301–4341): Originally applied in wartime, amended in 1933 to classify the domestic population as “enemies” for purposes of financial control.

- Emergency Banking Relief Act (1933, Pub. L. 73-1, 48 Stat. 1, codified primarily at 12 U.S.C. §§ 95a–95b and 50 U.S.C. App. § 5(b)): Amended the Trading with the Enemy Act and permanently delegated to the President sweeping powers to regulate and control banking, currency, gold, silver, and financial transactions during a proclaimed national emergency.

- House Joint Resolution 192 (1933), Public Law 73-10 (codified at 31 U.S.C. § 5118(d)(2)): Abolished the gold clause, declaring that all debts, public and private, are payable in discharge with legal tender rather than gold.

Equally significant, 18 U.S.C. § 8 defines what qualifies as an obligation or other security of the United States:

“The term ‘obligation or other security of the United States’ includes all bonds, certificates of indebtedness, national bank currency, Federal Reserve notes, Federal Reserve bank notes, coupons, United States notes, Treasury notes, gold certificates, silver certificates, fractional notes, certificates of deposit, bills, checks, or drafts for money, drawn by or upon authorized officers of the United States…”

Taken together, these provisions prove that every “obligation” — including those arising in Court — is treated as a security of the United States, monetized and discharged through the credit system established after 1933.

This is not “theory” — it is law and practice. From the Miller Act (40 U.S.C. §§ 3131–3134), which mandates bid, performance, and payment bonds in contracts, to 31 U.S.C. §§ 9301–9309, which governs sureties and bond approvals, the framework is well established. Even Fed. R. Civ. P. 17(a) requires that “an action must be prosecuted in the name of the real party in interest” — a phrase that ties directly to entitlement under 28 U.S.C. § 2042.

Every State mirrors this structure, with statutes authorizing clerks to receive, deposit, and often invest registry funds. Florida Statute § 28.33, for example, allows clerks to invest registry moneys and even retain interest; Utah Code § 78B-5-804 directs clerks to deposit funds into a court trust fund; and California Government Code § 16305 requires state money to be held in trust accounts.

The unavoidable conclusion is that courtrooms are bonded, securitized, and monetized enterprises. Judges and clerks, by presiding over cases that generate registry funds, hold undisclosed financial interests requiring disqualification under 28 U.S.C. § 455. By default, the STATE (corporation/ens legis/FICTION/charter) presumes itself trustee and beneficiary of these funds. Yet the statutes confirm that the real party in interest — the living man or woman — may petition and claim entitlement.

1. Every Case Generates Bonds

1.1. Court proceedings are not just legal disputes — they are financial contracts underwritten by securities.

1.2. Each case is underwritten by three primary bonds, identical in structure to federal procurement:

- Bid Bond (SF-24 equivalent): Filing of a complaint, charge, or motion constitutes the “bid.” Your signature and appearance create a negotiable instrument under UCC § 3-104(a):

“…‘Negotiable instrument’ means an unconditional promise or order to pay a fixed amount of money… payable to bearer or to order…” - Performance Bond (SF-25 equivalent): The clerk guarantees the case will proceed to judgment. This is the “performance obligation,” monetized as a bond.

- Payment Bond (SF-25A equivalent): Guarantees officers of the court, attorneys, and related parties will be compensated.

2. Statutory Authority for Deposits

2.1. 28 U.S.C. § 2041 – Deposit of moneys in pending or adjudicated cases:

“All moneys paid into any court of the United States, or received by its officers, in any case pending or adjudicated in such court, shall be forthwith deposited with the Treasurer of the United States, or a designated depositary, in the name and to the credit of such court.”

2.2. 28 U.S.C. § 2042 – Withdrawal:

“No money deposited shall be withdrawn except by order of court… any claimant entitled to such money may, on petition to the court and upon notice to the United States attorney, obtain an order directing payment to him.”

Fact: Every case creates a deposit in the Court Registry Investment System (CRIS), and the “real party in interest” may lawfully claim it.

3. Investment and Monetization

3.1. 28 U.S.C. § 2045 – Interest and dividends:

“The court may[must] order that the interest and dividends accruing on sums invested… be paid into the Treasury of the United States.”

3.2. Guide to Judiciary Policy, Vol. 13 (Financial Management): Directs clerks to deposit registry funds into CRIS, where they are automatically invested in U.S. Treasury securities.

3.3. Once deposited, funds are converted into instruments assigned CUSIP numbers and traded/settled as securities.

4. Suretyship and Bond Law

4.1. 40 U.S.C. §§ 3131–3134 (Miller Act):

Requires that federal construction contracts be backed by “a performance bond and a payment bond” (bid bonds also being required at bidding).

4.2. 31 U.S.C. §§ 9301–9309 (Sureties and Bonds): Defines corporate sureties, bond approval, and liability.

- § 9304(a): “When a law of the United States requires a surety bond, the bond may be provided only by a surety company that is approved by the Secretary of the Treasury.”

Fact: Court clerks function in a similar surety capacity when converting filings into bondable securities.

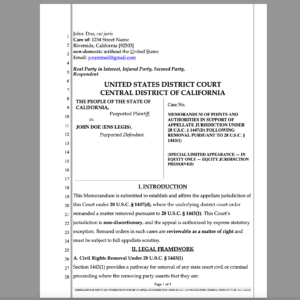

5. Real Party in Interest

5.1. Fed. R. Civ. P. 17(a):

“An action must be prosecuted in the name of the real party in interest.”

This establishes that only the real party in interest — the party with a true legal or equitable claim — may prosecute or control an action.

5.2. 28 U.S.C. § 2042 confirms that only the entitled claimant may withdraw deposited funds from the court registry:

“…any claimant entitled to such money may, on petition to the court and upon notice to the United States attorney, obtain an order directing payment to him.”

Read together, Rule 17(a) and § 2042 establish that the real party in interest has the right of withdrawal and claim to any funds or securities held in the registry.

5.3. UCC Article 9 (Secured Transactions) further clarifies the position of the real party in interest. UCC § 9-315(a)(1) provides:

“…a security interest or agricultural lien continues in collateral notwithstanding sale, lease, license, exchange, or other disposition thereof unless the secured party authorized the disposition free of the security interest…”

This means that a secured party of record retains a perfected interest in the collateral (here, the bonds, deposits, or securities generated by the case), even if the State or court attempts to treat them as its own property.

5.4. By filing and perfecting a security agreement and financing statement (UCC-1), the private party establishes themselves as the secured party creditor, which positions them not only as the real party in interest but also as the lienholder over the financial proceeds of the case.

5.5. Fact: If you do not assert your status as the secured party and real party in interest, the State presumes authority to administer the funds as trustee and to act as beneficiary of the bonds. If you do assert it — supported by Rule 17(a), 28 U.S.C. § 2042, and UCC § 9-315 — you establish superior standing to claim the proceeds.

6. Judicial Conflicts and Fiduciary Duty

6.1. 28 U.S.C. § 455(b)(4):

“He shall also disqualify himself… [when] he knows that he, individually or as a fiduciary, … has a financial interest in the subject matter in controversy or in a party to the proceeding.”

6.2. Canon 2, Code of Judicial Conduct: Judges must avoid even the appearance of financial conflict.

Fact: The existence of registry funds and bonds gives judges and clerks an undisclosed financial interest in every case, creating fiduciary conflicts.

7. Discharge and Obligation Law

7.1. UCC § 3-603(a):

“If tender of payment of an obligation to pay an instrument is made… the obligation of the obligor to pay interest after the due date on the amount tendered is discharged.”

7.2. 31 U.S.C. § 5118(d)(2):

“An obligation… may be discharged by payment, dollar for dollar, in United States coin or currency…”

7.3. 31 U.S.C. § 3123(a):

“The faith of the United States Government is pledged to pay, in legal tender, principal and interest on the obligations of the Government…”

7.4. 12 U.S.C. § 411:

“Federal Reserve notes… shall be obligations of the United States… and shall be redeemed in lawful money on demand.”

7.5. 12 U.S.C. § 412:

“Any Federal reserve bank may make application to the local Federal reserve agent for such amount of Federal reserve notes… Such application shall be accompanied with a tender to the local Federal reserve agent of collateral in amount equal to the sum of the Federal reserve notes thus applied for… The collateral security thus offered shall be notes, drafts, bills of exchange, or acceptances acquired under the provisions of this Act…”

7.6. HJR 192 / Public Law 73-10 (1933), codified at 31 U.S.C. § 5118:

“Every provision contained in or made with respect to any obligation which purports to give the obligee a right to require payment in gold… is declared to be against public policy… every obligation shall be discharged upon payment, dollar for dollar, in any coin or currency…”

7.7. 18 U.S.C. § 8 (Obligation or other security of the United States defined):

“The term ‘obligation or other security of the United States’ includes all bonds, certificates of indebtedness, national bank currency, Federal Reserve notes, Federal Reserve bank notes, coupons, United States notes, Treasury notes, gold certificates, silver certificates, fractional notes, certificates of deposit, bills, checks, or drafts for money, drawn by or upon authorized officers of the United States…”

Fact: These provisions establish that all obligations in the United States are treated as securities, issued and discharged through credit. Under 12 U.S.C. §§ 411–412, Federal Reserve notes come into circulation only against pledged collateral (notes, drafts, and securities). Since HJR 192 / Public Law 73-10 abolished gold clauses, every obligation — including judicial bonds — is monetized, securitized, and discharged in credit. Courts, through registry deposits under 28 U.S.C. §§ 2041–2042, operate within this framework, monetizing each case to satisfy the ongoing public debt system.

8. Some State-Level Parallels

|

State |

Statute / Rule |

Key Provision & Notes |

Strength as Parallel |

|

Florida |

Fla. Stat. § 28.33 |

“The clerk may invest moneys deposited in the registry of the court … and shall retain … 10 percent of the interest accruing on those funds …” Online Sunshine |

Strong — explicitly allows registry funds to be invested and addresses interest allocation. |

|

Florida |

Fla. Stat. § 28.24 |

Governs “receiving money into the registry of court” and associated fees. Online Sunshine |

Moderate — addresses how moneys are received in registry. |

|

Florida |

Fla. Stat. § 43.19 |

Governs disposition of unclaimed monies held in court registry after 5 years. |

Moderate — addresses what happens when registry funds are not claimed. |

|

North Carolina |

NC Uniform Trust Code, Chapter 36C |

Applies to express trusts, including trusts created by judgment, decree, or by court order. |

Weak to moderate — indirect parallel via trust law, not explicit registry deposit law. |

|

Utah |

Utah Code § 78B-5-804 |

“The clerk shall deposit the money in a court trust fund … to be held subject to the order of the court.” |

Strong — direct statute about depositing funds in a court trust fund under court direction. |

|

Utah |

Utah Code § 78-27-4 |

“Any person depositing money in court … the clerk shall deposit the money in a court trust fund or … to be held subject to the order of the court.” |

Strong — older codification of a similar rule. |

|

Kentucky |

Kentucky Court Rules (Registry Funds rules) |

Effective Dec. 1, 2016: rules governing receipt, deposit, and investment of registry funds under court rules. |

Moderate to strong — court rule (not statute) but explicit registry fund rules. |

|

Alabama |

(No strong state statute found) |

Alabama federal court local registry rules require court order before deposit; registry funds held via federal system. |

Weak — mainly federal-court registry practice, not explicit state statute for state courts. |

Undeniable Conclusion

Every judicial case in the “United States” is bonded with bid, performance, and payment bonds, following the mandatory structure established in federal procurement under the Miller Act (40 U.S.C. §§ 3131–3134). These bonds are not theoretical but operational: they form the commercial foundation of every proceeding.

The clerk of court, acting as a fiduciary and surety, converts the filings and signatures into securities, which are:

- Deposited under 28 U.S.C. § 2041, which requires that “all moneys paid into any court of the United States, or received by its officers, in any case pending or adjudicated in such court, shall be forthwith deposited with the Treasurer of the United States, or a designated depositary, in the name and to the credit of such court.”

- Withdrawable only by the entitled claimant under 28 U.S.C. § 2042, which states: “any claimant entitled to such money may, on petition to the court and upon notice to the United States attorney, obtain an order directing payment to him.”

- Invested under 28 U.S.C. § 2045, which authorizes that “the court may order that the interest and dividends accruing on sums invested… be paid into the Treasury of the United States.”

These deposits are held and pooled in the Court Registry Investment System (CRIS), monetized through U.S. Treasury securities, and assigned CUSIP identifiers for settlement and trading in the securities market.

By operation of 31 U.S.C. §§ 9301–9309 (Sureties and Bonds), judges and clerks function as corporate sureties administering the securities of each case. This creates undisclosed financial interests that fall squarely within the disqualification mandate of 28 U.S.C. § 455(b)(4):

“He shall also disqualify himself… [when] he knows that he, individually or as a fiduciary, … has a financial interest in the subject matter in controversy or in a party to the proceeding.”

Moreover, Fed. R. Civ. P. 17(a) declares:

“An action must be prosecuted in the name of the real party in interest.”

Read and comprehended together with 28 U.S.C. § 2042 and UCC § 9-315(a)(1) (which affirms that a “security interest… continues in collateral notwithstanding… disposition thereof”), it becomes undeniable that the real party in interest and secured party creditor retains superior claim to the bonds, deposits, and securities generated by the case.

Federal law confirms that all such bonds and instruments qualify as obligations of the United States:

- 18 U.S.C. § 8 defines “obligation or other security of the United States” to include “all bonds, certificates of indebtedness, national bank currency, Federal Reserve notes, Federal Reserve bank notes, coupons, United States notes, Treasury notes, gold certificates, silver certificates, fractional notes, certificates of deposit, bills, checks, or drafts for money, drawn by or upon authorized officers of the United States.” Court-generated bonds and securities fall squarely within this definition.

- 31 U.S.C. § 3123(a) pledges: “The faith of the United States Government is pledged to pay, in legal tender, principal and interest on the obligations of the Government issued under this chapter.” This statute guarantees payment on the securities generated, monetized, and deposited through judicial proceedings.

This entire system is the direct consequence of the emergency financial legislation of the 20th century:

- Federal Reserve Act of 1913 (12 U.S.C. §§ 221 et seq.): Created the Federal Reserve System and established Federal Reserve notes as obligations of the United States (12 U.S.C. §§ 411–412).

- Trading with the Enemy Act of 1917 (50 U.S.C. §§ 4301–4341): Extended in 1933 to classify domestic “persons” as “enemies” for purposes of financial control.

- Emergency Banking Relief Act of 1933 (Pub. L. 73-1, codified at 12 U.S.C. §§ 95a–95b and 50 U.S.C. App. § 5(b)): Gave the President sweeping control over banking and financial transactions during national emergency.

- House Joint Resolution 192 (1933), Public Law 73-10 (codified at 31 U.S.C. § 5118(d)(2)): Abolished the gold clause, mandating that all obligations public and private be discharged dollar-for-dollar in legal tender, not gold.

Undeniable Fact: Since 1933, all debts and obligations have been transformed into securities payable in discharge. The bonding of court cases, the deposit of funds under §§ 2041–2042, and their monetization through CRIS are the judicial enforcement mechanisms of this credit-based public debt system.

Therefore, the unavoidable and undeniable conclusion is this: Courtrooms are not merely forums of justice but bonded, securitized, and monetized enterprises. Judges and clerks, by presiding over cases that generate registry deposits, hold concealed financial interests requiring disqualification. By default, the STATE — a corporation, ens legis, and fiction — presumes itself trustee and beneficiary of these bonds. Yet by law, under FRCP 17, UCC Article 9, 28 U.S.C. § 2042, 18 U.S.C. § 8, and 31 U.S.C. § 3123, the real party in interest — the living man or woman, properly asserting secured party status — may petition and claim the funds. Failure to do so leaves the State to administer and profit as trustee of your estate.